The Duterte administration continues to face the daunting task of striking a balance between ending labor contractualization, a campaign promise of the president that got many labor groups and low-wage workers to vote for him, and ensuring the competitiveness of local industries. To make up for the absence of a clear-cut, unified policy on contractualization, the labor department has been going after corporations practicing “endo” (or end of contract), a short-term work arrangement which violates workers’ right to job security. With regard Filipino migrant workers, the administration has undertaken concrete measures that uphold the rights and dignity of migrants such as its memorandum of understanding with the Kuwaiti government that aims to protect abused overseas Filipino workers in that country.

Updated as of July 31, 2018

CATHOLIC SOCIAL PRINCIPLE:

Integral Development Based on Human Dignity and Solidarity

Public policy and government programs must promote development that not only fulfills the material needs of citizens, but also affirms human dignity and freedom, integrity in governance, national sovereignty, and the spiritual dimension of human beings.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) Global Rights Index 2018 included the Philippines as among the 10 worst countries for working people. The ITUC Global Rights Index 2018 ranks 142 countries based on 97 international recognized indicators to determine of workers’ rights are protected in law and in practice. According to the report, Filipino workers are likely to face “intimidation and dismissals, violence, and repressive laws.”

Recognizing human trafficking as a “non-traditional security issue” and a problem “in parity with drugs”, the president committed to “intensify our war against human traffickers and illegal recruiters that prey on our migrants.” He ordered (albeit without a formal issuance) the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) and the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG) of the Philippine National Police (PNP) to investigate recruitment centers and “make rounds to make sure that they are not illegally operated.”

In the 2018 Trafficking In Persons Report (TIPR) of the US State Department, the Philippines remains in Tier 1, which indicates the government’s full compliance with the minimum standards for eliminating human trafficking.

Although the Philippines maintained its Tier 1 ranking, the 2018 TIPR noted that the government did not advance in terms of the “availability and quality of protection and assistance for trafficking victims.” These include specialized shelter care, mental health services, access to employment training and, job placement. The report also pointed out the lack of zealous investigation and prosecution of officials accused of trafficking crimes.

In February 2017 the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) issued Department Order No. 170, or the Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act No. 10911, also known as the Anti-Age Discrimination in Employment Act. Recently in June 2018, the Bureau of Working Conditions of DOLE released a statement reminding the public that age discrimination in workplaces is prohibited and encouraged the public to report non-compliant companies.

On August 25, 2017, DOLE released a Department Order No. 178 on safety and health measures for workers who by the nature of their work have to stand at work. The order implements “rest periods or cuts time spent standing or walking, orders the installation of appropriate flooring to mitigate impact of frequent walking, provides for accessible seats during rest periods, provides for tables with adjustable heights to allow workers to alternately sit or stand while performing their tasks, and implements the use of footware that is practical and comfortable” (e.g., use of heels that are wedged and not higher than one inch).

On October 18, 2017, Department Order No. 184 was signed to provide occupational health and safety measures for workers who spend long hours sitting at work, such as those engaged in computer, administrative, and clerical work. The order requires employers to allow desk workers to have five-minute standing break every two hours. Other directives include ergonomic-friendly work stations, tasks that allow mobility, and health-related activities such as calisthenics and dance lessons.

To assist the 30,000 workers displaced by the closure of Boracay Island, which took effect on April 26, the following government agencies offered jobs and other forms of assistance:

- Before temporary closure, DOLE promised to provide emergency employment to about 5,000 residents (2,000 of which are members of the indigenous community) to clean up the island. In June, DOLE released ₱14.58 million for the Emergency Employment Program or Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa ating Disadvantaged/Displaced Workers (TUPAD). It was used to pay the wages of the program’s first batch of beneficiaries numbering to 1,688 for the period April 26 to May 31, 2018. Another 1,292 workers were hired to be the second batch of TUPAD beneficiaries. Cash assistance was also to be made available by DOLE to about 18,000 registered workers and 5,000 informal sector workers. The subsidy for registered workers amounts to ₱4, 205 per month for a period of six months, and a one-time cash assistance of ₱6,000 for part-time workers. As of June 29, DOLE Secretary Bello announced that only 3,600 beneficiaries have applied for the cash assistance.

- DPWH hired 40 residents for its road clearing operations.

- DSWD has three programs to help displaced workers in Boracay: Sustainable Livelihood Program (SLP), Assistance to Individuals in Crisis Situations (AICS), and Cash for Work (CFW). As of June, the following were the recorded beneficiaries of the programs:

- 2,958 residents received the livelihood grant amounting to ₱15,000 each

- 10,274 individuals were provided with transportation assistance amounting to ₱24.8 million

- 3, 924 individuals were provided with educational assistance amounting to ₱8.8 million

- 694 individuals were provided with medical assistance amounting to ₱2.1 million

- 1,898 individuals were hired under the Cash for Work Program

The order of the president to close Boracay island displaced more than 30,000 workers. Of this, about 17,000 were employed in establishments (e.g., hotels, restaurants, bars) and 17,000 were considered indirect workers (e.g., masseurs/masseuses, sand castle makers, tattoo artists). Even before the closure took effect, mass layoffs of workers were reported. Local business groups and labor organizations criticized the government’s lack of clear and comprehensive set of guidelines on how to assist displaced workers will be assisted.

President Duterte signed into law Republic Act 10968 which institutionalizes the Philippine Qualifications Framework (PQF). By ensuring the quality of education and training systems, the PQF will help increase the chances of skilled workers and professionals of getting hired abroad because the education qualifications they earned in the Philippines will be recognized by foreign employers. With their qualifications at par with international competency standards, OFWs will have enhanced “cross-country employability.”

The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) has streamlined its processes (e.g., one-stop shop center, online registry for seafarers) and reduced requirements (e.g., overseas employment certificate for returning workers), following the order of the president to eliminate red tape in government.

In December 2017, DOLE launched the first phase of the iDOLE OFW Identification Card System. The system will allow overseas Filipino workers (OFWs), beginning with returnees, to transact with agencies online instead of going to offices to avail of travel tax and terminal fee exemptions, among other services.

In January 2018, the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) launched an online portal where first-time OFWs can apply for a passport.

Through Executive Order No. 44, President Duterte greenlighted the acquisition of the Philippine Postal Savings Bank (Postbank) by the Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP) to serve as a bank for OFWs and their families, a campaign promise of the president. The Overseas Filipino Bank (OFB) is “dedicated to provide financial products and services tailored to the requirements of overseas Filipinos, and focused on delivering quality and efficient foreign remittance services.” Launched on January 18, 2018, the OFB can help OFWs and their families start a business by providing them low-cost financing or loans, without the cumbersome process often experienced when accessing loans from private banks. It also aims to increase the savings of expatriate workers by helping them invest in capital markets and by offering them shares of stock of the bank. OFWs sending their remittances to their dependents through the OFB will also enjoy lower charges. The OBF would address the banking needs of an estimated two million Filipinos working overseas, including immigrants, whose remittances contribute to the economy. In April 2018, remittances sent through banks amounted to US$2.35 billion which is 12.7 % higher compared to the same month last year while personal remittances amounted to US$2.6 billion, a 12.9% growth of the same month last year.

DOLE has yet to release the guidelines for the issuance of identification cards to OFWs (called iDOLE ID) that will facilitate their government transactions (loans, claiming of benefits, renewal of employment certificates, etc.). The pilot phase of the system started in mid-July 2017. OFWs, recruitment agencies, and migrant rights advocates complained that contrary to the announcement of the DOLE that the OFW ID is free, the card costs ₱501, excluding the delivery fee.

Alarmed by the increased number of incidents of sexually abused and maltreated Filipino workers, including four domestic workers who committed suicide and one who was found dead in a freezer, DOLE issued Administrative Order No. 25-2018 that temporarily suspended the deployment of workers to Kuwait “pending investigation of the causes of deaths of about six or seven of our OFWs.”

On February 12, 2018, a “total ban” was ordered on new workers migrating to the Middle East country to ensure the “safety and the welfare of our OFWs” and to “send a strong message to the government of Kuwait and other Arab countries that the protection and security of our OFWs is foremost in our policy.” Responding to concerns of recruitment agencies sending workers to Kuwait that the deployment ban would affect skilled workers (e.g., information technology professionals, store managers, electricians, plumbers), DOLE clarified that those with working visas and plane tickets will be allowed to leave.

Since the announcement of the total ban, the government has repatriated more than 5,000 OFWs from Kuwait, including undocumented workers who availed of Kuwaiti government’s amnesty program, which permitted them to leave the country without exit visa and dues for their illegal stay. The OWWA provided financial assistance for livelihood of up to ₱20,000 to each repatriated worker.

DOLE sent a task force to the Middle East in February 2018 to look for ways for government to effectively address problems faced by OFWs. The said group will also study the termination of the “kafala” practice, which “requires a company or employer to sponsor foreign workers in the validation of their alien work visas and residency” and “often blamed for the exploitation of OFWs” as it treats OFWs like properties that can be traded. The recommendations will be included in the employment terms in bilateral agreements to be presented to governments receiving OFWs.

“You come home and I will sell my soul to the devil to look for money so that you can come home and live comfortably here.”

President Duterte to OFWs in Kuwait, February 13, 2018

In a speech during a gathering of his supporters on March 21, 2018, President Duterte presented a list of demands to the Kuwaiti government that will ensure the humane treatment of Filipinos. Among the demands would be the following:

- workers’ passports must not be confiscated by employers

- workers must be guaranteed adequate sleep

- workers must also have a day off for them to go to church

- workers must also be allowed to cook their own food

- workers must be allowed to use and keep their cellphones so they can keep in touch with their families

Despite the diplomatic dispute between the Philippines and Kuwait, following a controversial “rescue” of distressed OFWs from their employers’ homes, the two governments signed on May 11 the memorandum of agreement that would ensure better treatment of Filipino domestic workers in the Gulf state. Salient features of the agreement include ensuring the employer provides Filipino workers with food, housing, and clothing, and registering the worker in the health insurance system, employers cannot confiscate the OFWs’ passports and other travel documents, transfer of workers to another employer should be with the consent of the OFW or with the go-signal of the Philippine Overseas Labor Office (POLO), and a mechanism must be established to provide 24-hour assistance to OFWs.

“As I said, we are not slaves. The only sin of these Filipinos is poverty.”

President Duterte, March 2

Following the signing of the memorandum agreement, DOLE lifted the deployment ban of domestic workers to Kuwait through Administrative Order No. 254-A, series of 2018. In June, the POEA also released Memorandum Circular No. 10, series of 2018, listing the guidelines for recruitment agencies on the resumption of the deployment of domestic workers in Kuwait which took into account the provisions agreed in the labor deal.

CATHOLIC SOCIAL PRINCIPLE:

Love of Preference for the Poor

Public policy and government programs must be oriented first of all toward meeting the needs of the most vulnerable and marginalized in society.

In May 2018, the president signed Executive Order No. 54 approving the ₱1,500 across-the-board increase in employee’s compensation (EC) monthly disability pension of all permanent disability pensioners and qualified beneficiaries in the private sector. The order also approved the increase in the amount of carer’s allowance given to EC permanent disability pensioners, and reimbursement rates for professional fees of physicians and physical therapy sessions.

Through the Relief Assistance Program (RAP) of the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA), a total of 19,201 undocumented and stranded OFWs in the Middle East were repatriated with the help of government from July 2016 to March 2017, following massive job loss in the region as a result of the global oil crisis. From July 2017 to October 2017, DOLE facilitated the return of 36,438 OFWs, among them were the 10,011 undocumented migrant workers in Saudi Arabia who were allowed leave without sanctions. Upon their return, the repatriated workers received financial and livelihood assistance, legal counseling, stress debriefing, and appropriate health services.

DOLE, through the OWWA, issued new guidelines for extending loans and benefits for OFWs who lost their jobs and returned to the country without receiving their wages. These include an increase in the “enhanced livelihood assistance” and a reduction of interest rates imposed on loans accessed from government-owned Landbank. For example, the non-cash livelihood package/assistance extended by the OWWA to returning OFWs through the “Balik Pinas! Balik Hanapbuhay! Livelihood Program” has been increased from ₱10,000 to ₱20,000. From January to March 2018, a total of ₱7.58 million was distributed to 379 returning OFWs under the program.

In his second State of the Nation Address (SONA), President Duterte announced that the assistance funds for distressed OFWs will be increased “from ₱400 million to more than ₱1 billion.” According to the DFA, the funds will be used to improve Assistance to Nationals (ATN) services of embassies and consulates general which include legal representation, monitoring of court cases, medical treatment and hospitalization, and facilitation of repatriation.

CATHOLIC SOCIAL PRINCIPLE:

Love of Preference for the Poor

Public policy and government programs must affirm human labor as the most important element of production, establish fair compensation that allows workers to raise families within a decent standard of living, protect the rights of workers to self-organization, and create opportunities for employment and livelihood with dignity.

Major wage and benefit orders under the Duterte administration include:

- In September 2017, the Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board for the National Capital Region (RTWPB-NCR) approved Wage Order NCR-21 which increases the daily minimum wage of NCR workers by ₱21. This increases to ₱512 the previous daily minimum salary of ₱491 for more than six million minimum wage earners in 17 cities and municipalities in Metro Manila. The minimum wage for those in the nonagricultural sector shall be ₱512 or ₱502 for the basic wage plus ₱10 for the cost of living allowance (COLA). Those in the agricultural sector and in retail or service establishments employing 15 workers or less and in manufacturing establishments employing less than 10 workers shall be entitled to ₱475, composed of the ₱465 basic wage and the ₱10 COLA. The wage rates also apply to all minimum wage earners in the private sector in the region regardless of their position, designation, or status of employment and irrespective of the method by which they are paid.

- In December 2017, the RTWPB-NCR issued a wage order increasing the monthly minimum wage of domestic workers or “kasambahay” in Metro Manila from ₱2,500 to ₱3,500. This new wage order applies to both stay-in and live-out domestic workers.

- In January 2018, the president signed Joint Resolution No. 1 of the Congress which authorized the increase in base pay of the military and uniformed personnel in the government.

- In July 2018, there were nine regional wage boards that approved an increase in workers’ basic pay. Of the nine regional wage boards, five have already implemented the increase.

The president has technically not fulfilled his promise yet to public school teachers because even though salaries did increase in January 2017 and January 2018, the pay increase, not only of soldiers and public school teachers but also of civilian government personnel, was the result of the Aquino administration’s Executive Order No. 201, issued in February 2016. The third installment of four trances to be implemented until 2019 under the said order caused the salary increase in January 2018.

DOLE issued Department Order No. 162, series of 2016 in July 2016, directing its regional directors to stop accepting applications from new third-party service providers (i.e., subcontractors). DOLE also banned from its job fairs enterprises engaged in the practice of contracting and subcontracting employment.

On March 16, 2017, DOLE issued a new order that sets stricter guidelines for contractualization. Through Department Order No. 174, series of 2017, the DOLE stressed that labor-only contracting, or the practice in which an agency “merely recruits or supplies workers to perform a job or work” for an employer, is the form of contracting that is prohibited. In labor-only contracting, the agency “does not have substantial capital or investment which relates to the job, work or service to be performed.” (“Endo” or the “end of contract” scheme is also restricted by the new department order, as it prohibits the continuous hiring by a manpower agency [contractor/subcontractor] of a worker under a repeated contract of short duration, usually five months.)

The department order prohibits the following:

- labor-only contracting;

- farming of work through “cabo“;

- contracting out of job or work through an in-house agency;

- contracting out of job or work through an in-house cooperative which merely supplies workers to the principal;

- contracting out of a job or work by reason of a strike or lockout, whether actual or imminent; and

- contracting out of a job or work being performed by union members if this will interfere with, restrain, or coerce employees in the exercise of their rights to self-organization.

According to DOLE, as a result of DO 174, some 70,000 contractual workers have been regularized during the first year of President Duterte.

To demonstrate its resolve to put a stop to unlawful labor contractualization, DOLE ordered several companies to regularize its employees:

- PLDT was ordered in July 2017 to regularize almost 9,000 employees who were under contracting and subcontracting arrangements but were performing jobs directly related to the company’s business. DOLE also directed PLDT and its 47 contractors to pay ₱77.5 million in overtime, holiday, and 13th month pay, service incentive leaves, and unauthorized deductions to 2,500 employees.

- Two Japanese-owned firms in Laguna were ordered to give regular employment status to their workers. Terumo Philippines corporation, which manufactures medical supplies and equipment, was ordered to regularize 1,048 workers. Toyo Seat Philippines Corporation, which is engaged in the business of automotive interior parts, were along with its 14 contractors, directed to regularize 284 laborers.

- Coca-Cola Femsa Philippines, Inc. (CCFPI) was ordered to regularize all of its 675 contractual workers. The company, however, refused to carry out the order and laid off in March 2018 600 employees who, according to labor groups, were those covered by the DOLE order.

- Jollibee Foods Corp., was ordered to regularize more than 7,000 workers.

- NutriAsia Inc with its three contractors, namely the Alternative Network Resources Unlimited Mutlipurpose Cooperative, Serbiz Multi-Purpose Cooperative, and B-Mirk Enterprises Corporation, were ordered to regularize 914 of their workers. (Despite these DOLE orders, there are companies that continue to resist the regularization of its workers. For instance, in July 2018, violence escalated in a strike being conducted by NutriAsia workers in Marilao, Bulacan. They are protesting for the termination of the company’s labor group leaders, as well as its unfair labor practices. The company had denied these claims.)

The House of Representatives passed on third reading House Bill No. 6908 which does not completely abolish contractualization but “expressly prohibits” labor-only contracting. Under the proposed measure, contractual labor is legal only if allowed by the labor department. Contractual employees are also to be regularized after having worked for six months. The bill includes provisions on giving benefits accorded regular employees to contractual workers, too, and compensating a worker on probation with at least a month of service but to be terminated ahead of the six-month probation period, with an amount equivalent to a half-month salary per month of service. This provision aims to prevent the practice of terminating probationary workers before regularization. President Duterte in his third SONA reiterated his call for Congress to “pass legislation ending the practice of contractualization once and for all.”

After flip-flopping on whether to issue an executive order that would end labor contractualization, one of his campaign promises, President Duterte signed on May 1, 2018 Executive Order No. 51, which bans illegal contractualization and ensures workers’ right to security of tenure. Labor groups were not satisfied with the EO, saying that what it prohibits is already in the Labor Code. The president, a few days later after the release of EO, admitted that the order he signed has “no teeth” and called on Congress to enact a law that will put an end to contractualization.

Although House Bill No. 6908 addresses some issues related to labor contractualization towards effecting regularization, it appears to be “institutionalizing” job contracting, and may be open to circumvention and abuse. This concern was raised by party-list representatives who wanted a total ban on contractualization, which the president promised to do within the first week of his administration.

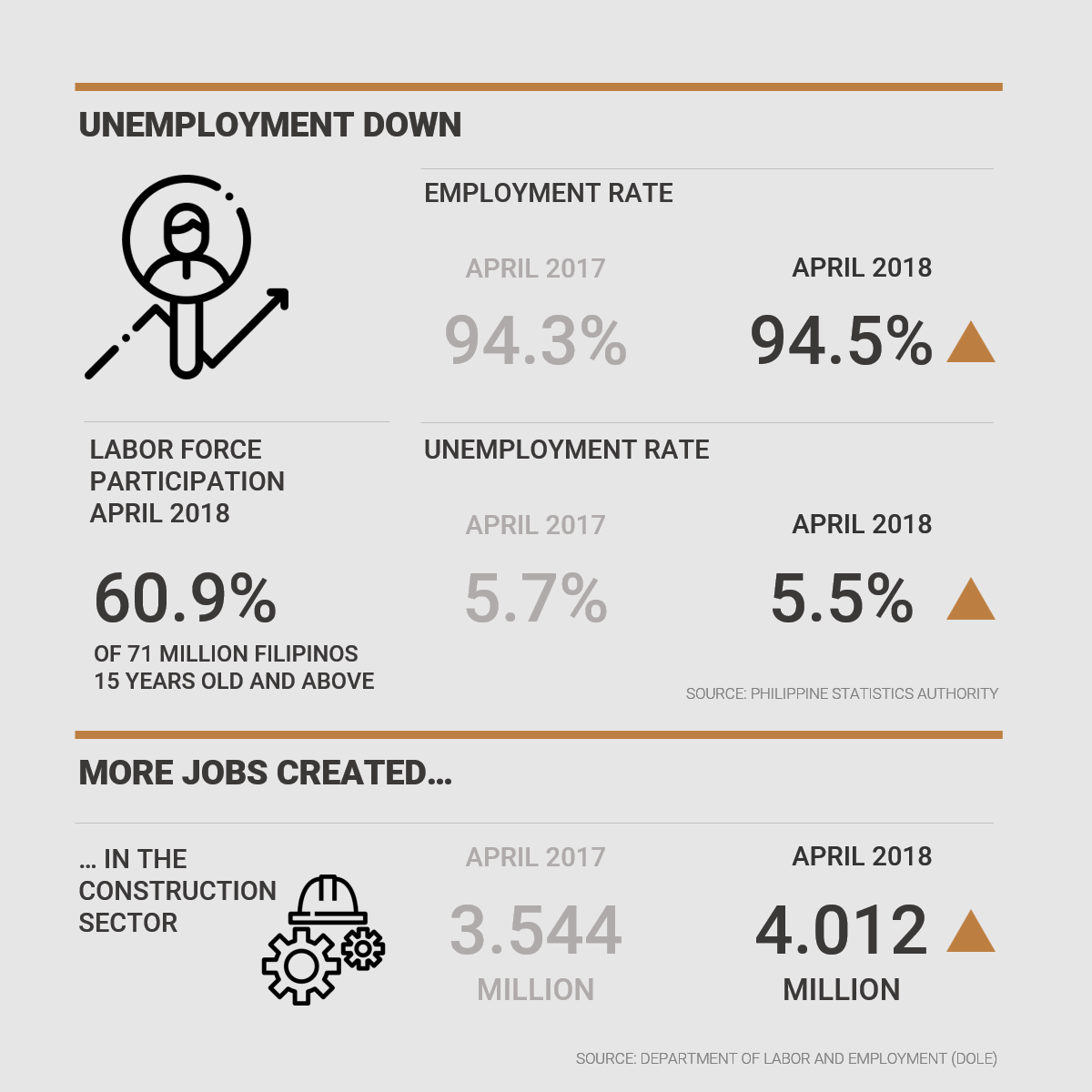

The unemployment rate in the country further declined to 5.5% in April 2018, compared to 5.7 % in April 2017. This means that the number of those who do not have work and who are looking for employment declined from 2.7 million to 2.36 million Filipinos. NEDA indicated that jobs from the infrastructure boom, which generated 468,000 jobs, contributed to this slight decline. The decline in unemployment figures is because a greater number of Filipinos went overseas in 2017. Nearly 100,000 more Filipinos went abroad and became overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) last year, according to the latest report from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

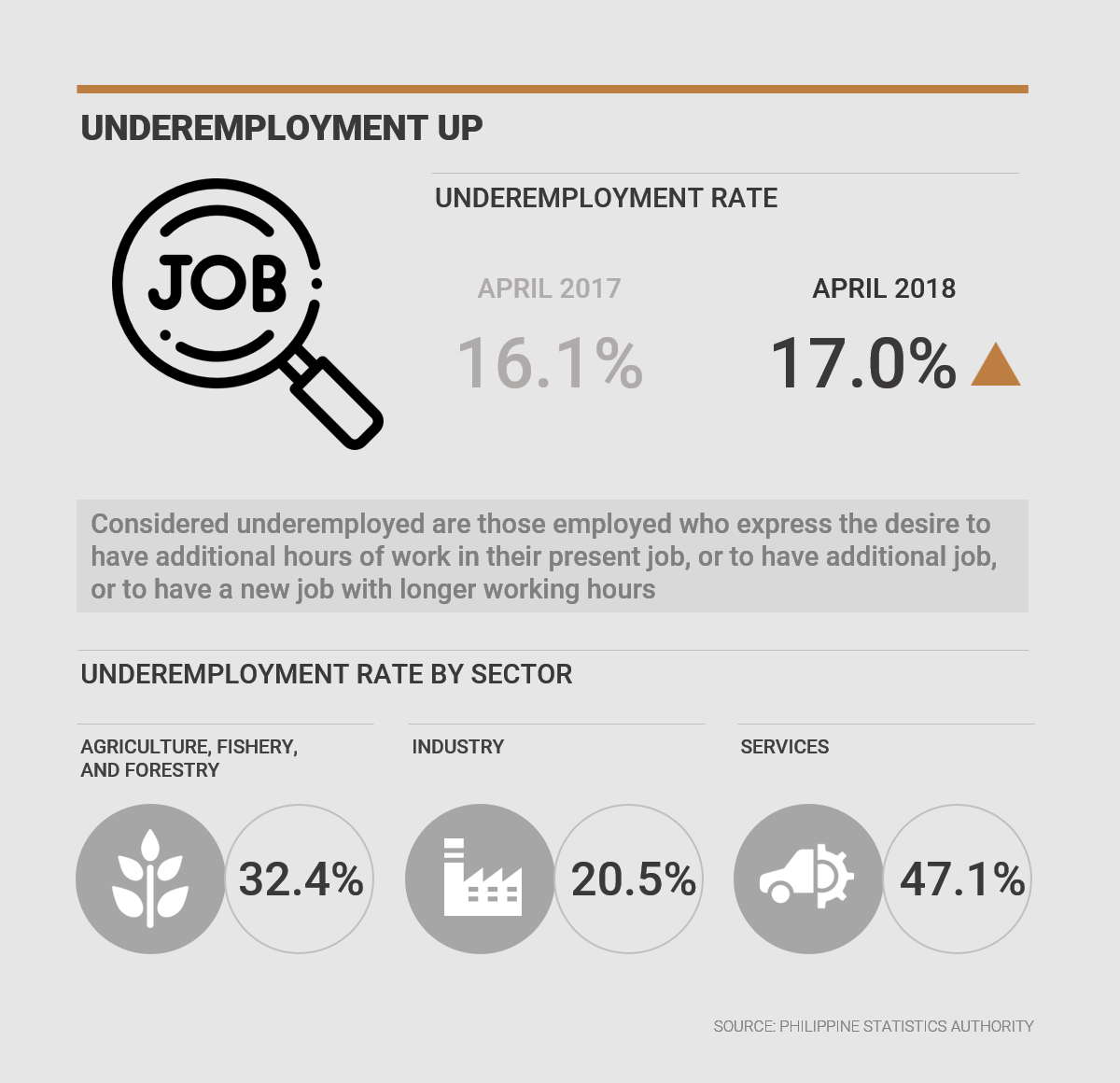

The underemployment rate (the proportion of those who have jobs and are looking for additional hours of work) increased from 16.1% to 17% during the same period. Workers reported a slightly less number of hours of work, from 41.3 hours per week to 40.6 hours.

The ban on overseas Filipino employment Kuwait imposed last February may have slightly affected employment figures in the first quarter of 2018, but this ban was lifted on May 15, 2018. According to the agreement signed with the Kuwaiti government on May 11, workers would be guaranteed food, housing, clothing, and health insurance and employment contracts would be renewed only with approval from Philippine officials.

The president is keen on establishing a dedicated department for the welfare of OFWs. Bills seeking the creation of a Department of Migration and Development have been filed at the House of Representatives and the Senate. According to House Bill No. 192, the department will integrate existing agencies and offices concerned with overseas employment to promote “protection, safety, development, [and] support of and for Filipinos (sic) migrants and their families.”

The creation of a dedicated department for OFWs might institutionalize what should be a short-term economic measure for Filipinos in the absence of adequate and gainful jobs in the domestic economy. This view has been conveyed by migrants’ rights advocates, non-government institutions, and even the labor secretary, who proposed that the OWWA and POEA be strengthened instead.

The Philippines signed the “ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers,” which commits member-states to develop a plan of action to implement the rights of migrants as specified in the “ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers.” Among the provisions of the declaration are the following:

- fair treatment of migrant workers with respect to gender and nationality;

- visitation rights by family members;

- prohibition against confiscation of passports and overcharging of placement or recruitment fees;

- protection against violence and sexual harassment in the workplace;

- regulation of recruiters for better protection of workers;

- right to fair and appropriate remuneration benefits and their right to join trade unions and association.

On March 21, 2018, the Senate adopted Senate Resolution No. 676 “expressing the sense of the Senate that the deployment of overseas Filipino household service workers to countries that do not afford migrants the same rights and work conditions as their nationals and allow the withholding of Philippine passports be totally banned.” In the House of Representatives, the Committee on Overseas Workers Affairs approved House Bill No. 7124, a bill seeking to amend Republic Act No. 8042 or the “Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995”, specifically its provisions on workers education programs, by mandating the POEA to publish and disseminate a standard handbook on the rights and responsibilities of Filipino migrant workers.

For its part, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) will establish a “migrants workers’ rights observatory” that includes “a system to integrate a reliable baseline as a starting point for a systematic monitoring of compliance of obligation fulfillment of Filipino migrant rights by duty bearers.”

Although the ASEAN has a Committee on Migrant Workers that will monitor whether the member-states implement the commitments made and draft an instrument that will ensure the welfare of migrant workers, the pact is non-legally binding, that is, “the responsibility to meet such commitments falls under the self-awareness of each member state.” The consensus is also “silent on individual or collective procedures to complain in the face of unexpected, unfair treatment,” which is not clearly defined in the pact.

For the Duterte administration, “Build, Build, Build” program would generate at least 1.063 million jobs a year and would discourage skilled construction workers from seeking employment abroad and encourage migrant workers to return.

Presenting the “Build, Build, Build” program as a solution to problems faced by repatriated OFWs, as the DOLE and DOF do, loses sight of the need for sustainable jobs. In one hearing of the House Committee on Overseas Workers’ Affairs, a party-list representative said that jobs that the “Build, Build, Build” program would generate are “project-based, low-paying jobs which will not solve the woes of repatriated OFWs.” The labor secretary admitted that although the priority of the Duterte administration is “to recall or repatriate all our workers abroad, because we know the social implications of parents leaving their family just to look for jobs,” opportunities for gainful employment are still lacking in the country.